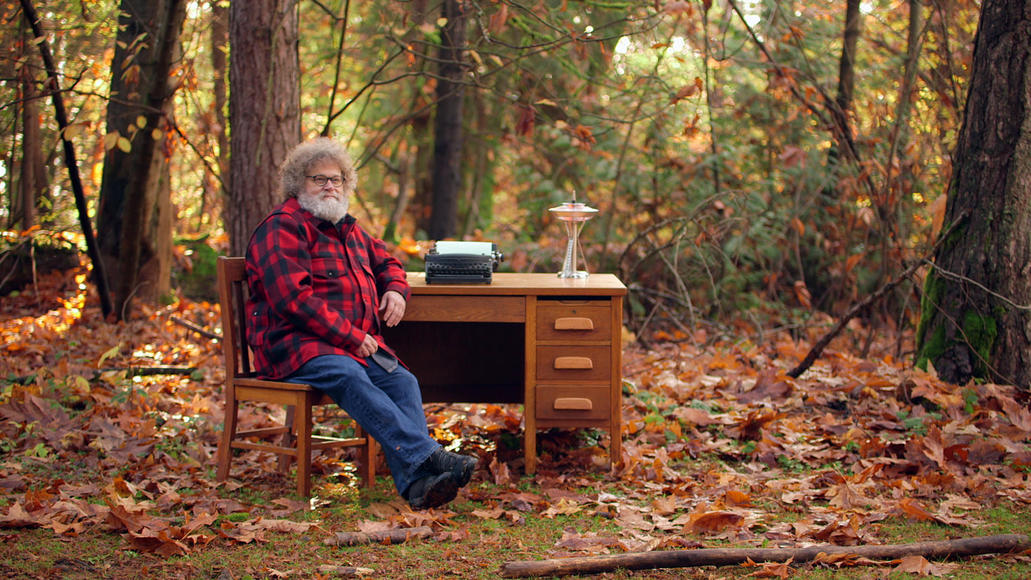

Mossback answers a few more of your questions

Knute Berger answers a few additional questions submitted by the audience during the "Finding Your Roots Washington" event.

On January 21, Knute Berger, AKA Mossback, hosted a virtual event with KCTS 9, “Finding Your Roots Washington: Old Growth to New Beginnings.” Attendees submitted a host of wonderful questions for Berger and our guest speakers to answer live during the event. Due to time constraints during the virtual event, they weren't able to get to all of them. Our resident Mossback has selected a few of the most intriguing outstanding questions and responded here.

Q: From Nicole Klein, West Seattle: For All: in such an innovative, and resource-rich city - would you say that this forward-thinking spirit does not value history, or 'ancestor' as much as other cities? Which cities or cultures should we aspire to be like?

A: I have two thoughts. One is that an advantage of frontier towns was that people could reinvent themselves, escape debt, jail or marriages they left “behind” back east. Western cities were often falsely seen as blank slates—places without history. Seattle, being a young city (founded in 1851) has often been thought as having no history worthy of commemorating, unlike say much older cities like Boston or Philadelphia, let along European cities. Civic boosters and developers saw this as an advantage: the past could not hold us back. Even now, historic preservationists are seen as people determined to hold us back from change. Still, there is a long history of preservation and nostalgia too. The first lamenting of a structure to be torn down in Seattle was in 1866 when Seattleites were saddened at the loss of Yesler’s Cookhouse, a structure that had acted as the city’s first gathering place. It was only 14 years old, but for young Seattle, is was a major landmark! I think we could be more like San Francisco in making our history more visible with building plaques and markers, wayfinders that tell us about the indigenous history of this place as well as people and events in more recent history. A decade ago I proposed that we name our alleyways and even our numbered streets because so much of our last century of history is not reflected on the street grid. Our history is everywhere and should be more visible.

Q: From Kazue Nakahara, El Cerrito, CAI taught at Queen Anne High on Queen Anne Hill in Seattle. How did it get that name? Also, Seattle supposedly has seven hills. What are their names?

A: Queen Anne Hill was named after a style of architecture popular when it was developed. Its original name was Eden Hill—clearly not named by people who had to walk up it every day. As to the seven hills, that story is more complicated than it appears because there is no clear consensus on which seven people were or are talking about—there are at least 12 hills in Seattle, and some hills, like Profanity Hill, are rarely referred to as such in modern times. The best write-up I’ve seen on it is by geologist/historian/author/walking tour guide David Williams. Consult him—the author of Too High and Too Steep about regarding hills like Denny Hill-- on all things related to Seattle’s geologic history.

Q: Paula Foy, Bainbridge Island: I'd like to ask about the history of coal mining in Newcastle and other areas. My grandmother was born in Newcastle, to a mining family I think, even though I and my family are from Michigan and Iowa.

A: In the 1860s, locals discovered there was coal in them thar hills and foothills of the Cascades. For a century, places like Black Diamond, Newcastle, Coal Creek, Renton, the ghost town of Franklin, and others were home to extensive coal mining. Miners came from all over the country—and the industry played a major role in Seattle’s history. In the 1880s, these mines provided most of the coal for the West Coast, and Seattle’s first railroad was built to move coal from the mines to Elliott Bay for shipping more expeditiously than barging it across Lake Washington and Lake Union. We did a Mossback’s Northwest episode, “When Coal Was King in Seattle” about that. For Newcastle specifically, you might want to check out the Newscastle Historical Society website for more information.

Q: Lisa Reager, Seattle: I'd like to hear more about women voting in the 1800s.

A: Women got the vote in the Washington Territory in the 1880s, but it was overturned (twice) by the end of the decade. This timeline from the Washington Secretary of State’s office gives a quick picture of the sequence of events, as well as the voting history in the state. Washington women played a pioneering role in the Suffrage movement, and this article in Crosscut, “The Road to Women’s Suffrage Began in Washington State” by Carolyn McConnell, puts the efforts here in context with the national movement, and profiles some remarkable sisters who advocated for it well before statehood. It is well worth a read.

Q: Lori Michetti, Wallingford: For Josephine Ensign: How successful was the poor farm and could those work today?

A: I emailed Prof. Ensign and here is her reply: “Here is what I would say (an extremely complex answer distilled down): Poor farms in general throughout the United States, located in smaller and more agricultural areas versus large urban areas where poor houses were located, were adaptations of similar efforts in England and Scotland, part of the English Poor Laws. This "indoor relief" (as opposed to "outdoor relief" or "welfare checks" as used today) was meant to be a means of social control and punishment for the poor. They even included--as was the case at the King County Poor Farm and Hospital--pauper cemeteries and crematoria--again, as psychological punishment for the poor. The King County Poor Farm and Hospital were located in the Georgetown area along the (before 'straightened') Duwamish River on 160 acres of land, some of which was cultivated by early Seattle settlers, mainly as a fruit orchard and for growing hops. When the Sisters of Charity of Providence took on the farm and hospital, they did contract out land use to nearby farmers and grew some produce (such as potatoes) for the sisters and hospital residents and sold the excess. The 'indigent pauper' patients of the hospital were, for the most part, much too sick to work on the farm. The King County Hospital at Georgetown was never a convenient place since it was at a distance from Seattle, but it was successful as an ancillary hospital for TB patients and elderly patients once Harborview was opened in Seattle.”

Looking back at our region's past

You loved the images shared during the event, so we're sharing a few of them here! Check out this fantastic collection of historic photos from our community partners for this event, MOHAI and the Black Heritage Society of WA. These are just snapshots of some of the history discussed during the event.

Publications authored by our speakers for learning more about the region's past:

- Catching Homelessness: A Nurse's Story of Falling Through the Safety Net- Josephine Ensign

- In Search of the Racial Frontier, The Forging of a Black Community- Quintard Taylor

- Don't Blame the Tech Bros for the Housing Crisis- Margaret O'Mara